Visitor's guide

>> HISTORY

The African Museum of Lyon seeks to showcase West African cultures through the objects that comprise its collection, in order to broaden our vision of the world and promote intercultural understanding.

The Society of African Missions, based in Lyon, founded the museum in 1863. The collection grew over time through the missionaries’ sojourns in Africa, notably in Dahomey (present-day Benin). This collection, one of the oldest and richest of its kind, is unique in that it focuses on West African objects. The museum has existed in its present location since 1930, with three exhibition floors currently displaying 2,200 of the 8,000 objects in the museum’s collection.

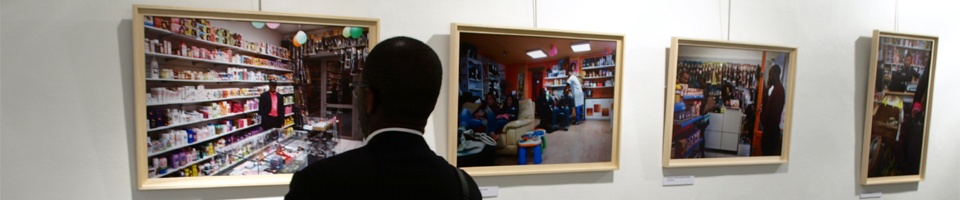

Today, the museum aims to serve as a space for dialogue, exploring the ever-changing nature of and ongoing connections between African and European cultures. To this effect, it creates temporary exhibits, conferences, and events that engage with traditional African arts as well as contemporary artistic production from both the African continent and the diaspora.

>> OVERVIEW

The museum’s permanent exhibitions begin on the second floor of the building and continue up three floors. The first level explores Daily Life in West African villages, from around the time of the missionaries’ activities, mid-1800s to mid-1900s. The second level centers on Social Life, displaying objects that play an important role in institutions such as chieftaincy, trade, and seasonal ceremonies. Religious and Artistic Life is the theme of the third level, where you will find masks, vodun pieces, and other objects that animate sacred practices. These are the gems of the collection, valued by museums today for the quality of the craftsmanship and their formal beauty.

The thematic divisions are porous, as religion, art, social life and daily life overlap. The same object can have different functions in each of these spheres. By concentrating on a distinct aspect in each level, we hope to show the multidimensionality of the objects in our collection.

>> FLOOR 1 -- DAILY LIFE

Human-made objects result from both a creative will and a basic need: to gather, cook, and preserve food; to shelter and take care of the body; to communicate with others. While these basic needs exist throughout the world, each culture responds differently to them, according to their specific environment. The collection in this level bears witness to the ways West African men and women produced highly functional and beautiful objects out of natural materials.

Throughout this floor, you will see calabashes turned into containers and household utensils (VITRINE 8). The gourd is cinched as it grows to create a specific shape, and once it reaches the desired size, the pulp is scooped out and the gourd dries in the sun. Decorations can be carved on the outside once the gourd dries. These designs may refer to proverbs, as is commonly done among the Fon people of south Benin.

Another prominent material throughout this floor is bronze, as seen in the small figurines in the shape of men, women, and animals. These figurines, from the Fon people, represent historical moments, social events, and proverbs (VITRINE 2, 7, 9, 14, 19). Today, in the museum, these constructed scenes are used to illustrate village life and they are a good example of the products created through the lost wax method. This method, which was highly practiced in the Kingdom of Dahomey, was used to cast bronze and other metals (VITIRINE 20 and photo series on opposite wall). A labor-intensive process, this method produces detailed, one-of-a-kind ornaments. Each clay mold can only be used once, since it must be shattered to retrieve the metal object.

Weaving, whether on a loom (VITRINE 21, 25) or by hand, produces many household objects as well. Cotton is woven into thin strips, and these strips are sewn together to make a larger cloth called a pagne. A common weaving material displayed throughout this floor is raffia. These are palm frond fibers that can be dried and dyed according to the need, woven into baskets and bags (VITIRINE 24), used in masking costumes, or beaten into threads to weave a softer cloth (VITRINE 22).

>> FLOOR 2 -- SOCIAL LIFE

In addition to meeting basic needs, man-made objects help organize social life. The objects displayed on this floor circulated in trade, in the chiefs’ courts, and in seasonal ceremonies. Many of these objects’ forms, in addition to their practical function, communicate particular meanings. The changes over time in the objects’ designs also illustrate contact and exchange with different cultures.

The first vitrine (1), toward the left at the top of the stairs, contains brass bracelets (manicles), rods, and cowrie shells. Trade flourished across the Sahara before the Europeans arrived in the 15th century, with cowries serving as monetary reserves and trade currency. The Portuguese introduced brass to the trade, and the metal alloy quickly became a highly desired good. Brass was traded in manicles, because in this bracelet shape it could be easily transported, worn as jewelry, and smelted into other objects.

In the next series of vitrines, you’ll find small brass weights to measure gold (VITRINE 2-4), from the Akan people who live in present-day Ghana and Ivory Coast. An area rich in gold mines, it became the home of numerous Akan groups, including the dominant Ashanti empire. Gold has a fraught history in this region, since it was a motor in the slave trade, both within Africa and across the Atlantic Ocean.

Gold, however, also fueled creativity and artistic development. Because gold dust could be used as a trade currency, the Akan developed a system of weights that set a standard unit of measure to ensure fair and accurate trading (VITIRINE 4). Produced with the lost wax method, each skillfully crafted brass measure weighs a precise amount, regardless of its shape. Each trader would bring his own set of weights, to test against each other.

Earlier weights, from the 15th and 16th centuries, were cast in geometric shapes (VITIRINES 7-12, 19). As artistic technique deepened, figurative weights in the shape of humans, plants, and objects began to appear (VITIRINES 13-18; 20-23). Both the geometric weights and the figurative weights evoke proverbs that speak to Akan cultural values, with later weights creating complex, multiple-figure scenes (VITIRINE 8).

While gold was a symbol of power, being the embodiment of kra, the life-power of the sun, there are many other objects that belong exclusively to the royal court. In the powerful Akan states, when a chief comes to power, he sits on a carved wooden stool (VITRINES 27 items 7, 8; 29 item 8). The more powerful the chief, the more decorated the stool. After the death of a chief, his stool is retired and kept as part of the royal treasure. Conserving the ancestral seats of power ensures, one hopes, continued rule.

At events such as funerals and annual celebrations, the chief will be accompanied by a procession; the bronze figurines in Vitrine 25 illustrate these courtly scenes. Large umbrellas carried by his entourage provide shade for him, and remind the people that likewise, the chief provides shelter and security for them. Ceremonial rifles, staffs, and arms exemplify the kingdom’s strength. Many of these items are carved or decorated with gold or bronze emblems. Animal shapes such as elephants, leopards, and lions allude to the chief’s might, while other forms can reference military victories or other historical events.

>> FLOOR 3 – RELIGIOUS LIFE

In addition to helping us meet physical needs and build a social environment, objects also play a role in building and maintaining a community of people. Objects can animate spiritual beliefs, commemorate important moments, and negotiate conflict. The objects in the third level of the museum speak to this intangible side of communal living. They also, however, speak to ideas about beauty and art in both West Africa and Europe.

You’ll be able to see numerous masks from different ethnic groups on this floor. Each has important differences in their style, meaning, and use. But one element the masks all have in common is that they are normally part of a larger costume that covers the whole body, made of cloth, raffia, or other materials. The sculpted wooden faces were easier to transport and conserve, and were the part of the costume that were most valued by art enthusiasts. Thus, in most museums today, this is the only part of the mask that remains.

Each mask is itself the embodiment of a spirit. Their main purpose was not to disguise the wearer. Rather, the person wearing the mask temporarily becomes the vessel through which the mask can communicate a message to the community, often through dance and song and accompanied by a cohort of other masks.

To left at the top of the stairs and around the first corner, on the right hand side you’ll see the brightly painted Gelede masks, made in the Youruba communities in Benin and Nigeria (VITRINE 15-18). These are often called helmet masks, for they sit on top of the head. A sheet of beads or a cloth drapes over the wearer’s face. The naturalistic facial features of the masks are not necessarily gendered as male or female. Though worn by men and boys, the Gelede traditions aims to honor the women in the community, and to appease the maternal forces that influence fertility and life. What distinguishes each mask is the decorations on top, which may be as varied as headdresses and colonial hats (VITRINE 16) or animals such as snakes, birds, or a man with his pig (VITIRINE 17, 18). In addition, the masks encourage harmony within the community, as they celebrate or criticize the leaders and social powers represented by the masks’ decorations in an entertaining manner. Their performance brings all members of the community together to remind them to resolve disagreements and treat each other as if they were children of the same mother.

In the next exhibition space toward the right side, you will find a group of much larger, more abstract masks (VITRINE 29-32). These masks, from the We people of the Southwest Ivory coast, play a role in mediating community issues as well. The justice mask (VITRINE 30) wears a necklace of branches whittled into the shape of panther teeth, suggesting it is a hunter and chief. This masks emerges when there is a conflict to be resolved in the community, determining the guilty party and imposing fines. To its left sits the begging mask (VITRINE 31). It comes out in times of hardship, and its jocular, jovial behavior encourages people to donate food or other gifts to share with the community.

To the right on the left-hand side of the window, is the collection of Kru (also known as Grebo) masks from Sassandra, a city in Ivory Coast (VITRINES 24-26). These are even less naturalistic that the We masks, the face constructed from simple geometric shapes: a cylinder for the forehead and eyes, a vertical box for the nose, a rectangle for the mouth and two stripes that form the teeth. These masks were highly influential in the early stages of modern European painting, as cubist painters were inspired by these masks to compose human features from abstract shapes.